Alabama may be a conservative state. But conservative activists still insist the textbooks here are too left-wing.

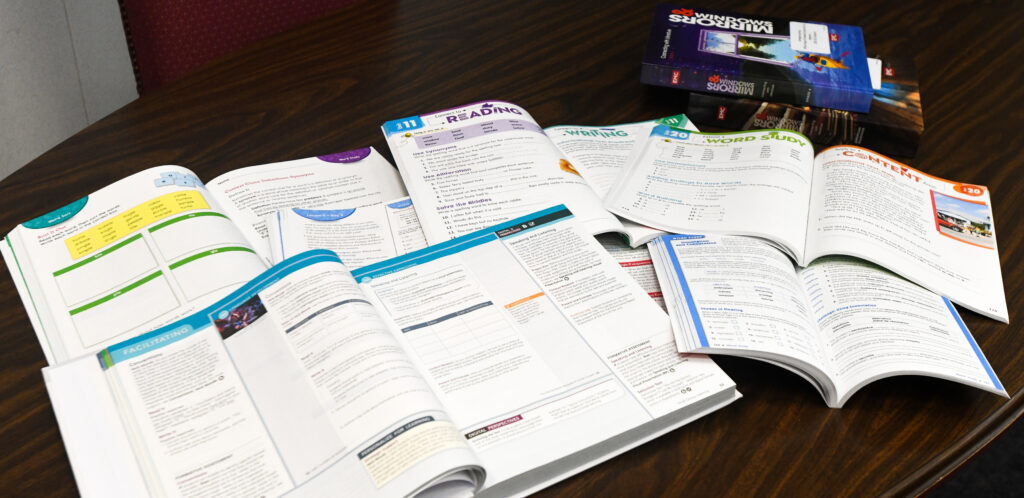

Earlier this year, the State Board of Education approved English Language Arts textbooks for kindergarten through third grade after a public hearing where critics suggested the books had too much Black history and multicultural stories.

These books had already been delayed after they were originally meant to be adopted in 2022.

Melissa Gates, who had identified herself as a member of Eagle Forum, said the books, called the Amplify Core Knowledge Language Arts, would “indoctrinate our children with DEI [Diversity Equity and Inclusion], SEL [Social Emotional Learning], woke agenda and grooming our little ones.”

Cathy Odom, who had identified herself as a resident of Mobile County, said the vetting process was unclear, and she had concerns about the content.

“And I thought personally there was too much Black history,” she said.

Those books are rated “green” on Ed Reports, a textbook evaluation site, in alignment with expectations for standards and research-based instruction.

The Eagle Forum of Alabama, a conservative organization who many of the speakers associated themselves with, did not return requests for comment.

Mark Dixon, head of A+ Education Partnership, spoke at the meeting to stress the expertise that went into the book selection process. The state approved two sets of textbooks. A district that had concerns about one could choose another.

These conversations are also happening amid a national conversation about equity and diversity in education. Last year, the Alabama Legislature approved a bill that restricted information about gender and sexuality in schools. This year, a bill restricting the teaching of so-called “divisive concepts” is making its way through the legislative session.

Despite the claims of activists, the Alabama textbook adoption process is a complex legal pathway with a number of steps to get books from the publisher into the classroom. While standards from Texas and California, two states with enormous influence over textbook content, play a role, the state uses several non-politicized checkpoints that can take months to complete.

Much like the rest of Alabama’s public education system, the textbook adoption process is a centralized system from the state level.

School districts can use state money to buy state-approved textbooks. But political attacks on state-level textbook adoption can be costly for local bodies. The state did not approve new textbooks for K-3 English Language Arts in 2022. That meant that no district could use state funds to purchase textbooks in the subject area.

The list only had one approved textbook due to requirements around copyright year.

Patrick Chappell, customer development analyst with Publisher’s Warehouse, which distributes textbooks in Alabama, said that the delay meant 80% of districts, many already dealing with funding issues, were due to update their textbooks.

Alabama State Schools Superintendent Eric Mackey said in March books that face opposition in Alabama may have been written for California, but he doesn’t know for sure. California has requirements for diversity in the texts.

“I don’t know that for sure, but I will tell you that some of the issues that we seem to deal with, I don’t want to say definitely, are because of other big states like maybe say California, that they put additional things in their standards,” he said. “The textbook companies write for those standards and then our, you know, those may not be as well accepted in Alabama as they are in California. Let’s put it that way.”

How new textbooks are selected

Every year, the State Department of Education revises the courses of study for different subject areas. These courses of study form the basis of what the state is looking for in textbooks, Chappell said.

The courses are revised every few years for each subject, but there can be changes to the schedule.

The Alabama Social Studies course of study has not been updated since 2010. According to Rebecca Griesbach at AL.com’s Education Lab, the course of study’s update was delayed for several years after a 2021 report from the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The report, while mostly positive, criticized elements of Alabama’s history curriculum, such as the teaching of “states’ rights” and slavery:

“However, there is a somewhat ambiguous reference to “states’ rights” in the fifth-grade standard on the causes of the Civil War, which should either be removed or more clearly subordinated to “the issue of slavery” to avoid misinterpretation (5.11). And the decision to lump together the many changes that have occurred in the seven decades of U.S. History “since World War II” is unfortunate (content standard 9).”

Alabama is scheduled to adopt new social studies textbooks for the 2024-25 year, according to the Alabama Course of Studies schedule, issued in May 2022. The textbooks are tied to the course of study renewal.

Chappell said that the state is working with the same textbook contracts from the Social Studies Course of Study renewal thirteen years ago.

Literacy textbooks have a slightly different process. The books that the textbook committee looks at must be approved by the Literacy Taskforce first, which ensures that the instructional materials follow the Science of Reading curriculum, which not all states mandate.

A long approval process

The process of approving a textbook can take a full year.

According to a guide from the Alabama State Department of Education, the department invites publishers to submit potential textbooks for an approved course of study in January. Publishers who are interested fill out forms signaling their interest in February, as the department develops criteria based on courses of study.

Carolyn Jones, state textbook coordinator with the Alabama State Department of Education, said that those courses of study are used when asked textbook publishers to bid.

“Once those are approved, then we send an email to the publishers that we have in our database stating that, you know, we’re getting ready to bid for textbooks and supplemental materials or whatever that subject area is,” she said.

Chappell said that publishers are asked to self-assess themselves on how they meet the state’s course of study criteria. Those are the same rubrics that the state textbook committee uses in their work.

In March, the Alabama State Textbook Committee, an appointed committee of 23 people, is formed. 14 members are appointed by the State Board of Education. Nine members are appointed by the governor. Each person serves a one-year term. The board is mostly nominated by Republican politicians.

Under the textbook law, four members are elementary teachers and four are secondary teachers. Those teachers are meant to represent the eight State Board of Education districts. Four members are from the state-at-large and can be classroom teachers or in the education field in an administrative or supervisory capacity. Two members are from higher education.

The committee reviews the books to ensure that schools meet the state courses of study requirements and make recommendations to the State Board of Education.

The committee has different criteria for different subject areas, and the list of textbooks– and some ratings– can be found on the Alabama State Board of Education website sorted by subject area.

Publishers deliver textbooks to the Department of Education in May. The textbook committee reviews proposals from June to August.

Supplemental materials, such as handwriting books, are not required to meet all of the stated requirements because they are not designed to be used without another textbook that does meet requirements.

Textbook companies will sometimes design their textbooks around a state’s course of study, but generally only for a large state like Texas or California, said Mackey.

“Texas and California are so big that the textbook companies generally build their books around the standards in those two states,” he said. “And, so, if you build your textbooks around the Texas or California standards, then what I’m told is you can sell enough textbooks in those two states to make it profitable, and, so what happens is most of the other states then have to figure out a way to make the Texas and California books match their standards.”

According to American Public Media, the high concentration of students in Texas and California means textbooks makers know they need to write textbooks that will be accepted by those states. Florida is also starting to impact textbook structure.

The three states made up a quarter of all textbook sales from March 2020-2021.

But any textbooks approved in Alabama need to meet Alabama standards. Jones said that the textbook committee does not use external reviewing of textbooks, such as Ed Reports.

“We may be looking at something specific for Alabama,” she said. “And when you look at Ed Reports to other states or whatever, their criteria may be different. So, just because that textbook gets a score on Ed Reports or any other, you know, organizations out there, other states does not mean that it’s going to get the same score here in Alabama.”

Jones said the textbook committee general meets four to six times a year for two- to three-day sessions.

In September, the textbook committee does a final review and prepares a list of recommended textbooks for members of the State Board of Education to consider at an October work session.

The Board formally receives the recommendations in November, though the list is supposed to be confidential. In December, the Board votes on recommended textbooks, and may take public input prior to the vote. The state can and often does approve multiple textbooks for different subject areas.

The schedule outlined above is the ideal, written schedule. Chappell said the last couple of years the State Board has not been ready to vote in December.

“Those delays hurt,” he said.

He said the longer the State Board waits to vote, the harder it will be for local committees to adopt in time.

“The State Board can move their timeline three months and local districts move it three months. You don’t move the start of school by three months. School’s going to start at the end of August. So, you end up in a situation where books can’t be delivered on time.”

He said these are all things they are currently working on.

The textbook pipeline

Most books that go into Alabama classrooms are purchased through the textbook depository Publisher’s Warehouse, a company based in Alabaster.

Chappell said that Alabama is one of a minority of states with an adoption process. School districts get $75 per student to purchase books.

“If you think back to college, how much books cost?” he said. “They’re not any cheaper.”

He said in 2021, the math textbook adoption year, the Warehouse did around $90 million in sales.

Chappell said the company tries to assist school districts that cannot afford to pay for large textbook orders each year by offsetting them with smaller purchases other years on payment plans. For example, a district may need a large expensive order of math textbooks one year, but a much smaller purchase of driver’s education books another year, depending on the adoption schedule.

“So as long as school districts are paying us something, we kind of work with them individually,” he said. “So, even the poorest school districts ought to be able to do something.”

He said they’re doing late textbook billing to help districts pay for their reading textbook.

Bart Reeves, Alabama Association of School Boards Assistant executive director for governmental relations, said that the system is equitable in that all districts receive the same amount, but districts begin with different resources.

“You’re going to have some systems that have more tax dollars that they can allocate towards textbooks,” he said.

Reeves used to serve on a local textbook committee when he was in a school district.

He said that while the system with payment plans with Publishers’ Warehouse works well, the $75 amount has been the amount for many years.

Local decisions

Local districts make the final decision on textbooks. State-approved textbooks can be purchased by districts with state funding, which tends to encourage districts to adopt the same texts.

Local districts are not meant to use any money to buy books rejected by the state committee, according to the Alabama State Department of Education State Textbook Adoption Process & Procedures Guide, provided by communications director Michael Sibley. It is not clear what if any sanctions exist for districts that do not comply.

Chappell said some local boards may use their own money to buy more supplemental materials, for example.

“You can always have local money added to the textbook budget,” he said.

Jones said they encourage the local textbook committees to operate concurrently to the state one, or else the local committees may not have enough time to go through their process. If local committees choose books from the state-approved textbooks, then they can use state funds.

Chappell said delays in the process hamper local committees’ ability to choose textbooks. “The state ought not to be adopting something in March,” he said. “They ought to be adopting something in November and December.”

Chappell said that he used to work in a school district, which is one of the higher ranked school districts in the state. He gave the example that the academic standards for some schools might be higher than the state’s standards. They would need to pick a book from the state-approved list to use state funds, but they can apply their own standards to pick a book from the list.

“The state is looking at a minimum criteria, (such as) ‘do these meet the standards,’ and the district should really have the stronger pull of really trying to match,” he said. “Because they’re not trying to just match to every place in Alabama, you’re trying to match to your unique subset in your school district with your teachers and students. So you know, it’d be a higher level of scrutiny in my mind.”

School districts can use state funds to buy textbooks off of the approved state list and can use local funds to buy off the list.

Reeves said local committees are tasked with deciding what textbooks work best for their students.

Reeves said he might have had all of his fourth-grade math teachers review all of the approved math textbooks to decide which one works best for their kids and recommend it to the local textbook committee. He said the local committee works with the superintendent and district’s curriculum coordinator to make final recommendations to the board.

“Does it cover our standards?” he said. “Is it the best for our community and is it the best for our kids? You know, is this going to raise the needle on student achievement?”

Alabama Reflector is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Alabama Reflector maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Brian Lyman for questions: info@alabamareflector.com. Follow Alabama Reflector on Facebook and Twitter.

This article was reposted from Alabama Reflector with permission under a creative commons agreement. Read the original article: https://alabamareflector.com/2023/05/23/how-does-alabama-choose-textbooks-slowly/

Jemma Stephenson covers education as a reporter for the Alabama Reflector. She previously worked at the Montgomery Advertiser and graduated from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.